We live in a time when baring your soul by writing a memoir has become so popular that bookshelves, literal and virtual, are awash with the genre. And importantly, they stock memoirs of ordinary people. There was a time when it was more common for only the very well-known to write memoirs. We read them to find out what was behind the gloss of fame.

But in the last few decades, that has changed. While celebrity memoirs and auto(biographies) are still hugely popular, ordinary accounts of everyday lives are devoured. Memoir as a genre has exploded. There are many courses devoted to the study of it, as well as some university degrees. The personal becomes universal: we read about the breakdown of someone’s marriage, or experience of widowhood to help us on our own journeys through grief, for example.

Let’s look at various categories of memoir writing, what point of view (POV) to use and how to mine your memory to feed your story, as well as some other issues.

Autobiography vs memoir

Firstly, it’s necessary to define this distinction. A memoir is usually themed and focused on one part of a life. An autobiography is usually the story of an entire life. So, you might be writing a memoir about adopting a child: your book would focus closely on this topic. You wouldn’t go into your childhood at length or how you met your partner, for instance. You might touch on these stories, but your main story would be focused on why you adopted, the journey to adopting, and what you have learned by adopting (for instance). As I say, you could touch on memories from your past, but you wouldn’t dwell there, your focus would be on this theme.

For example, in Joan Didion’s Blue Nights, her memoir of mourning her daughter, Quintana, who died at the age of 39, is heavily focused on the grief experience and Didion’s questioning of her own mothering of Quintana, with snapshots of their lives together, as well as her thoughts on aging. Similarly, Joyce Carol Oates’s A Widow’s Story focuses on a period of about six months following the death of her first husband. It focuses on her grief, although there are flashbacks and reminisces about her marriage.

It's important to note that memoirs usually focus on a time that changed everything in a person’s life.

Here is another look at these distinctions.

Telling the truth

This might be considered a given, but it’s worth repeating. A memoir is a story that’s true. That is the contract you enter into with your reader when you define your book as a memoir. That doesn’t mean that nothing has to be invented. Take dialogue, for instance. It’s very rare that you will have an actual transcript of conversations you have had. You might have kept a journal and recorded some of them there, or you might have court transcripts, but by and large you will be relying on memory. Some memoirists even put a disclaimer at the beginning of their books, saying that the conversations reported are amalgamations of memory. They might be approximations of the conversations, but it’s important to note that they are not solely invented. But neither are they invented. You need to tell the truth as much as possible. Not doing so can lead you into hot water.

For an example of what can happen, look at the case of James Fray. His memoir, A Million Little Pieces was published in 2003, which was marketed as a memoir of drug addiction, crime, and a journey to sobriety. Significant parts of this and a follow-up memoir, My Friend Leonard, were found to have been fabricated. The media fall-out was sensational, Oprah Winfrey excoriated him. Book deals were cancelled.

Bring your publishing dreams to life

The world's best editors, designers, and marketers are on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Define your theme, plot, use fictional techniques

When starting to write a memoir, you will need to define your theme: grief, divorce, adoption, moving to another country, discovering yourself through travel and so on.

It can sometimes be hard to define that theme. You may have a thread of themes eg in a divorce memoir, you might want to write about meeting your spouse, the marriage and then the divorce. All of these aspects relate to the theme of your divorce memoir.

A useful way of defining the theme of your memoir is to sum it up. If you were to tell someone what your book is about what would you say? That is most likely your theme. To take the divorce memoir above, you might say, “It’s about when I left my spouse and finally discovered who I really was. I took a trip through Africa and that changed my life.” This is very different from the hypothetical memoir described above, this is really the story of what happened after the divorce.

The next step is to plot your memoir. Today’s memoirs share a lot in common with fiction in terms of ways of telling the story. Plotting is as vital with outlining your memoir as a novel. List events as you would like to record, track your story beats, as well as the conflict and the resolution.

And, as with fiction, you will be using many fictional techniques: foreshadowing of events, dialogue, description, exposition. Although you’re telling a true tale, using all these techniques will make your writing pop.

Describe what you can experience through the five senses. Describe the ocean view before you as you contemplated divorce, or the taste of the tart lemon pie in your mouth when he said he had fallen in love with someone else.

As Judith Barrington writes in Writing the Memoir:

Although the roots of the memoir lie in the realm of personal essay, the modern literary memoir also has many of the characteristics of fiction. Moving both backward and forward in time, re-creating believable dialogue, switching back and forth between scene and summary, and controlling the pace and tension of the story, the memoirist keeps her reader engaged by being an adept storyteller. So, memoir is really a kind of hybrid form with elements of both fiction and essay, in which the author’s voice, musing conversationally on a true story, is all important.

POV is not something you might have to think hard about. With memoirs being first-person accounts, you are probably going to write in the first-person. But some memoirists have used third-person and it’s an interesting technique to explore. While Oates’s A Widow’s Story is told in the first person, there are times when she refers to ‘the widow’, as though looking in on this strange creature a ‘widow’. In Murray Bail’s slim memoir called He, Murray uses third-person "he" to tell his story. Meanwhile, Annie Ernaux in what many consider to be her magnum opus, The Years, also tells the story from the third-person as well as first-person plural ‘we’. Admittedly this book blurs the line between memoir and fiction. Here are two excerpts:

But unlike our parents, we didn’t miss school to plant colza, shake apples from trees, or bundle dead wood. The school calendar had replaced the cycle of the seasons.

The black-and-white photo of a little girl in a dark swimsuit on a pebble beach. In the background, cliffs. She sits on a flat rock, sturdy legs stretched out very straight in front of her.

Novelized memoir or autofiction

While Ernaux’s The Years blurs and blends genres, her A Girl’s Story is an example of a novelized memoir, or auto-fiction. This is a novel that draws very heavily from an author’s life but some or many parts of it are invented and heightened. It’s not all true—although much of it is. As a genre it’s not marketed or labelled as such, and is, perhaps more of a distinction that writers make of their work than readers.

Looking at A Girl’s Story, although it is labelled a novel, it uses the facts of Ernaux’s life as well as her name. Here is an extract in which the older ‘I’ of the story is describing her younger self. (Note that Duchesne is Ernaux’s maiden name.) This excerpt freely mixes first and third person, too.

Even without a photo, I can see her, Annie Duchesne, step off the train at S in the early afternoon of August 14. Her hair is in a high French twist.

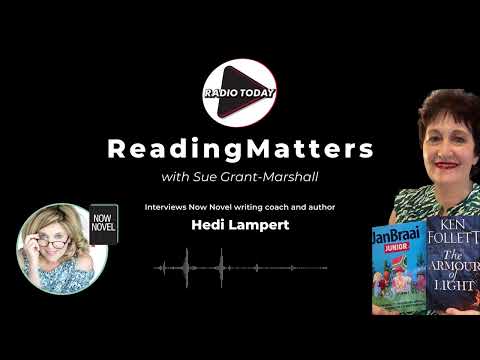

One of our Now Novel writing coaches, Hedi Lampert, has also written a fictionalised memoir, called The Trouble with my Aunt. In it Lampert takes the actual case of her aunt, born with Fragile X Syndrome and weaves it into a fictional story, undercut with much research into the syndrome. Speaking to Sue Grant-Marshall on Radio Today on the program “Reading Matters,” Lampert explains how to incorporate fictional elements into this genre:

There is a genre called the new autobiography. It is a sort of a fictionalized autobiography which sounds like a paradox. But when you take the devices that novel writers use in terms of creating drama, suspense, incorporating dialogue and certainly showing more than telling, there are a lot of things we as memoirists can learn from novelists and indeed even from filmmakers. When you incorporate those things, you can add elements of fiction and still very much tell a story that is hard-hitting and largely true. That is what I did with The Trouble with My Aunt. I incorporated quite a lot of science and genetics too, as well as romance, humor and nostalgia. I think it hits quite a lot of beats.

The process of creating the book took 15 years however, as Lampert kept returning to the story. Read our interview in our archive in which Lampert explains that she had been writing bits and pieces of it. It was only by giving herself some time off that she was able to sit down and write the book.

I think you have to be very brave to be a writer, to be an author. But like I said, for me it was easier because they had all passed away. I'm not quite sure how I would have dealt with it had my mom still been alive, had my grandmother still been alive. — Hedi Lampert

She further explains the genesis to Grant-Marshall:

My mother's sister had a genetic condition called Fragile X syndrome. It's actually more common than people realize. She never went to school, she was different. She was also lovely, she laughed very easily, she also cried very easily. She was rather entertaining but also, she was a lot of work. My mother grew up duty-bound to her and I watched this.

So I had the story and I wrote it all down. After doing various courses and trying to get it as best as I could, I realized that I still only had about 30,000 words and as a novelist, you know, you need at least 70 to 80,000 words. So I realized I had to actually draw in some drama that I had to make up and there was fiction that had to be incorporated. That's what I did and that's why it became more than a memoir, it became a novel.

You can listen to the podcast below.

Writing about people still alive

It was Anne Lamott who said in her writing guide, Bird by Bird: “You own everything that happened to you. Tell your stories. If people wanted you to write warmly about them, they should've behaved better.”

Still, it can be a thorny negotiation writing about people who are still alive, Lampert offers her own experience:

That's such a difficult one. And I mean, it certainly dogs many writers, not just biographers or autobiographers, because even people writing fiction fear that somebody they know will think that a character has been based on them. Number one is bravery. I think you have to be very brave to be a writer, to be an author. But like I said, for me it was easier because they had all passed away. I'm not quite sure how I would have dealt with it had my mom still been alive, had my grandmother still been alive.

Some memoirists choose to give the characters in their memoirs initials instead of names. Ernaux did this in Getting Lost, a book that describes her affair with a Soviet diplomat stationed in Paris, he is simply “S”. In Helen Garner’s three-volume published series of journals, she rarely gives full names, instead she uses initials. Her third husband was Murray Bail, but in her diaries he is “V”, her daughter Alice is “M”.

Pseudonyms can be used, of course. You can also combine a few characters into one as a composite—but make sure to mention this, of course. You could also ask people for permission to use their names, but they might be less likely to say yes if you’re writing about them in a harsh light!

Memoir in essays and travel

Another way of writing a memoir is to write a series of essays. You could collect previously published essays from journals and so on, and collate them into book form, using theme to guide you. Marcia DeSanctis does this in A Hard Place to Leave: Stories from a Restless Life, blending her travel narratives with personal stories in some of the pieces.

Another example of this type of memoir is Me Talk Pretty One Day by David Sedaris: Sedaris’s humorous collection of essays offer poignant reflections on his life, family and experiences living in France.

James Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son is a collection of 10 essays, many also autobiographical, including the title essay, about growing up under segregation.

It’s also important to consider that some travel narratives blend the genres of personal writing with travel, writing a travel story that is also about a personal journey and lessons learned and so on. A recent example from the 2000s would be Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat Pray Love, in which her journey is both a travel trip and a way of getting over her divorce, and then details meeting a new husband. Laura Fraser’s series of travel narratives, An Italian Affair and All Over the Map combine travel with very personal stories.

For a personal blog for tips on how to publish a memoir read co-founder of Now Novel Bridget McNulty's experience. She also gives advice on how to start writing a memoir.

8 ways to mine your memory

However, you want to tell your story and in whatever format, you are going to have to find ways to mine your memories. With a memoir you’re going deep into the nitty gritty of your experiences, and you may not remember or have all the facts to hand. Here are 8 ways to plumb those depths.

- Journaling and freewriting: journal and free write about significant events, people and emotions from your past. You could buy a special book and let the memories flow in journal notes. Or, freewrite with a prompt such as “I remember …” and see what comes.

- Conduct interviews: speak with friends, family members, or anyone else who was present during the events you are writing about.

- Engage with photographs and mementos: look at old photographs, letters, and other mementos from the past eg an old furry bear from your childhood. Describe the bear, use your five senses when describing it. You might be surprised at what associations you may make through describing this object that once meant so much.

- Practice visualization and meditation: use visualization and meditation techniques to transport yourself back to specific moments that you want to write about. Imagine lying in the sun in the yard behind the house, wearing your striped red bikini. Who was with you? What were you feeling?

- Explore personal archives and documents: look through diaries, letters or even old school projects, that can help you reconstruct the past. Beware though, when reading diaries, that you might find your memory contradicts the actual events of the past and you’ve remembered incorrectly. But this can be a starting point too, to mine that memory and see why you’ve misremembered.

- Try memory-prompting exercises: for example use memory jars, write short descriptions of memories on slips of paper and draw them randomly to stimulate recollection.

- Visit significant locations: return to places that hold special significance in your life. This can trigger vivid memories and emotions. You may find that a house that was so large is actually much smaller in reality and this might trigger another recollection. In any case, you will have some response to this place from the past which you can incorporate.

- Try mind mapping techniques: create mind maps to visually organize your memories. This can help you identify key themes and significant moments in your life. This will be useful when plotting your narrative.

Subscribe to our newsletter

One million authors use our writing resources to get their books published. Come join them.