If you know where your scene is headed but can’t figure out how it should start, you’re not alone.

The first few lines of a scene set the tone and establish important context — a big task for a short bit of text. This is your chance to get readers on the hook for the rest of your scene or chapter, so it’s critical to get it right. Luckily, we’ve assembled a list of the 5 best tips that great writers use to hook their readers from the second the curtain goes up.

1. Invite a nagging question

The first few sentences of a scene should leave readers bent on finding out what comes next. A great way to build suspense from the start is by putting a big question in readers’ minds — and implying that you’ll answer it later on.

🔖 Example: The Salt Eaters by Toni Cade Bambara

Are you sure, sweetheart, that you want to be well?

🔎 Why it works:

This opening sentence asks a simple question brimming with meaning that we won’t fully grasp unless we read on. The line of dialogue tells us — at the most basic level — that someone is unwell, and that the speaker doesn’t fully believe that person wants to recover. We’re drawn in by this tension, and the lack of context means we’ll need to listen to the characters in order to form our own opinions.

The use of “sweetheart” softens what would otherwise feel like an accusation and hints at an amicable relationship between the speaker and the addressee. It tells us that we’re not reading the start of a heated argument but that of a milder interpersonal conflict between people who care about each other.

Another feature that makes the opener successful is that it’s embedded in dialogue, driving us straight into the story’s action.

✍️ Master this technique

Question-based openings are most compelling when the question being asked holds greater implications for a character’s life. A mundane question, like “coffee or tea?” (unless the character’s life up to this moment has involved a grave battle between the two), will feel like filler and alienate a reader who wants to start getting to know your characters right away.

If you decide to start your scene with a question, be careful to strike a good balance between orienting readers to the situation and leaving them wanting more: if an opening is too confusing, your readers might grow frustrated. But if it’s too obvious, they might lose motivation to read on.

If your scene merits a clearer introduction, the next tip might be a better fit.

2. Set the scene with an “establishing shot”

For this tip, we’ll take a cue from a popular filmmaking technique. In movies and TV, an establishing shot indicates the location, time, and feeling of a scene.

This shot at the start of Fargo, for instance, reveals where we are (Brainerd), a bit about this place (it’s the home of Paul Bunyan, and judging by the size of that statue, they’re pretty proud of it) and the time of year (a cold, grim winter).

Similarly, you can start a scene in your story with a descriptive introduction that establishes place, time, and other details to anchor your readers in the world of your story.

🔖 Example: Paradise Rot by Jenny Hval

There, and not there.

Outside the hostel window the town is hidden by fog. The pier down below dissolves into the colourless distance, like a bridge into the clouds. At times the fog disperses a little, and the contours of islands appear a little way out to sea. Then they’re gone again. There, not there, there, not there, I whisper, leaning against the window, drumming my fingers against the glass in time with the words, dunk, du-dunk, as if I’m programming a new heartbeat for a new home.

🔎 Why it works

This establishing shot pans over the view outside our narrator’s window before turning inward to offer a glimpse into her mind.

First, it helps us visualize the setting — the sleepy pier, a cluster of islands appearing and disappearing through the fog. Hval doesn’t gloss over the haze by writing simply that it’s a cloudy day, nor does she bore us by describing the exact shape of every last island. Instead, we get a representative illustration — curated by the narrator.

As it goes on, the introduction hints at how Jo, the narrator, feels about what she’s seeing. “There, not there” is a subjective interpretation, not plain description. It suggests a shaky grasp on concrete reality — in this new home, Jo can only believe in what she sees. Now we share her disorientation and we’re curious to learn more — what is Jo doing in this foggy new place?

✍️ Master this technique

In the past, great novels indulged in lengthy, zoomed-out descriptions of setting. Entire chapters of The Grapes of Wrath and The Hobbit are devoted to scenery alone. But detached visual description has fallen out of favor among modern readers. If you want to write a successful establishing shot today, your description should reveal something about the character’s circumstances.

The challenge with an establishing shot is choosing which details to include: the introduction should make readers feel like they’re there without getting them bogged down in irrelevant details, but it also shouldn’t be overly general.

Note details that characterize the scene and offer a glimpse into the narrator’s mind, especially if they reveal a tension between the external circumstances of setting and the narrator’s internal circumstances.

Your establishing lines can include more than just visual description, though. The next tip will show you how to work multi-sensory description into your introduction.

3. Use sensory details to immerse readers

Sensory detail — especially detail that calls upon senses other than sight — can make your setting feel more real, drawing readers in.

This strategy works across genres: if your story takes place in a fantastical setting or somewhere that won’t be familiar to most of your readers, describing its smells and sounds will showcase your worldbuilding skills and make your setting feel more real. On the other hand, if your story takes place somewhere so familiar that it risks feeling mundane, adding sensory details can make it fresh and interesting.

Let’s take a look at an introduction that exemplifies the latter point.

🔖 Example: Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata

A convenience store is a world of sound. From the tinkle of the door chime to the voices of TV celebrities advertising new products over the in-store cable network, to the calls of the store workers, the beeps of the bar code scanner, the rustle of customers picking up items and placing them in baskets, and the clacking of heels walking around the store. It blends into the convenience store sound that ceaselessly caresses my ears.

🔎 Why it works

The author brings us to a familiar setting — a busy convenience store — but adds details that casual customers might not notice. The sounds are recognizable (we can all hear the scanner beep in our minds, right?) but the narrator delivers them in a unique way that tells us a little about her. Most of us probably wouldn’t think of the convenience store soundtrack as a “caress”, but this narrator genuinely seems to enjoy it. We might gather that she spends a lot of time in this convenience store, but she doesn’t seem to mind.

The author brings us to a familiar setting — a busy convenience store — but adds details that casual customers might not notice. The sounds are recognizable (we can all hear the scanner beep in our minds, right?) but the narrator delivers them in a unique way that tells us a little about her. Most of us probably wouldn’t think of the convenience store soundtrack as a “caress”, but this narrator genuinely seems to enjoy it. We might gather that she spends a lot of time in this convenience store, but she doesn’t seem to mind.

Now we’re immersed in the setting, we’ve learned something about our narrator, and we’re eager to uncover more context.

✍️ Master this technique

Like an establishing shot, the key to a sense-driven introduction is finding the right details to include. If Murata had written, “I’m in a busy convenience store and it’s loud”, we probably wouldn’t be quite as interested.

Choose details that the reader will be able to sink their teeth into, even if you’re writing about a world they’ve never experienced. Describing the petrichor of an enchanted forest or the sinister beeping of killer robots will make your world more convincing than explaining what everything looks like.

Sometimes, you’ll need to introduce new characters at the start of a scene. If that’s the case, the next two tips will help you make those introductions feel natural and compelling.

4. Introduce characters in action

Character introductions won’t necessarily appear at the start of every scene. But since they’re essential to those early scenes, we’ll look at a couple of ways to make them work. Readers should know who’s going to be involved in a scene pretty early on — when you’re introducing an important character, show them doing something that hints at who they are.

Action-driven introductions can reveal something about the character’s mannerisms or behaviors, foreshadow interpersonal conflict, and compel readers to turn the page.

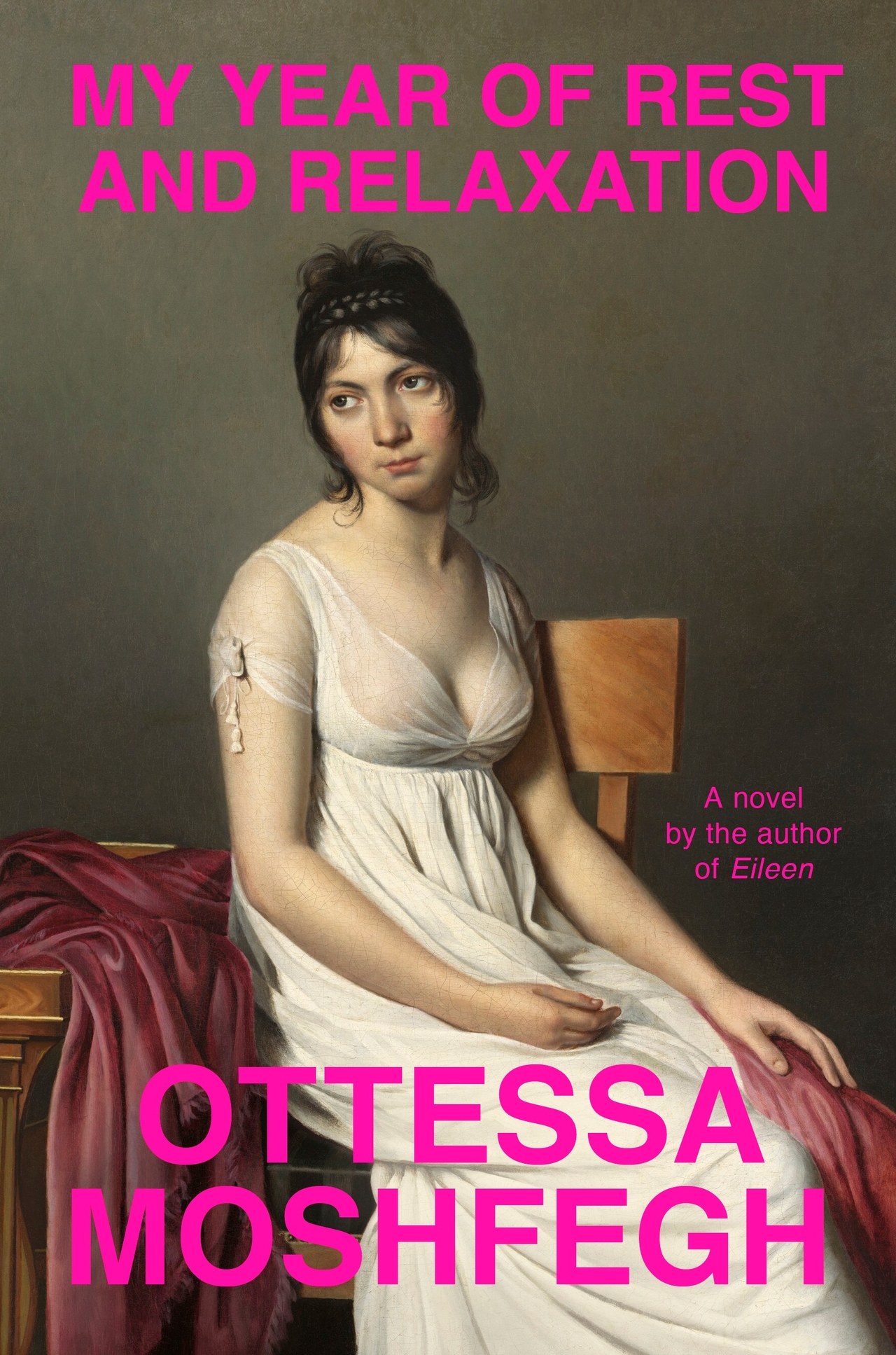

🔖 Example: My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh

Whenever I woke up, night or day, I’d shuffle through the bright marble foyer of my building and go up the block and around the corner where there was a bodega that never closed. I’d get two large coffees with cream and six sugars each, chug the first one in the elevator on the way back up to my apartment, then sip the second one slowly while I watched movies and ate animal crackers and took trazodone and Ambien and Nembutal until I fell asleep again.

🔎 Why it works

Moshfegh wastes no time in the opening lines of her book, which introduce us to the narrator’s strange compulsions. The specificity of the action verbs — “shuffle”, “chug”, “sip” — makes it easy for us to visualize the narrator’s behavior, even though we don’t have any other context.

Moshfegh wastes no time in the opening lines of her book, which introduce us to the narrator’s strange compulsions. The specificity of the action verbs — “shuffle”, “chug”, “sip” — makes it easy for us to visualize the narrator’s behavior, even though we don’t have any other context.

The opening word, “whenever”, lets us know that what we’re seeing described is a habit, not a one-time thing. And the rest of the clause, “whenever I woke up,” suggests that she spent a lot of her time asleep. We’re left to wonder about why she sleeps so much, and how she developed these behaviors. This introduction offers specificity without context — just enough information about the character’s behavior to draw us in; no extraneous detail.

✍️ Master this technique

Character-driven introductions are great for practicing the “show, don’t tell” rule: rather than telling your readers that a character is angry, for instance, show that character slamming the door or storming upstairs. Action tells us how the character feels, but it has the added bonus of showing us how they deal with their emotions — it’s also much more immersive than simple description.

Remember, action doesn’t need to be dramatic in order to be effective. My Year of Rest and Relaxation's introduction is a great example of action that’s vivid, but not overwhelming. A character’s first action on the page doesn’t need to reveal everything about them — you should aim to give readers just enough to get them interested.

Trust that your readers will be patient enough to accept new details as they become relevant — action that tells us everything at once will usually feel contrived.

5. Lead with a strong point of view

If your narrator has a strong point of view — a unique dialect, unusual beliefs, strong opinions, etc. — then starting inside their head is a great way to show it off. Scenes that highlight a character’s perspective might start with their inner reaction to a situation, or an internal monologue that reveals how they think.

Let’s analyze an example where internal monologue is rooted in action.

🔖 Example: Worry by Alexandra Tanner

I shut the door on her and try on her coat in the living room mirror. It goes better with my eyes than hers, and since I’m two inches taller than she is, it hits my legs in the right place. On me, it’s not so terrible. Maybe I’ll tell Poppy I think the coat’s disgusting, and once she stops wearing it out of shame, I’ll take it — but then how would I explain wanting something I’d insulted?

To avoid a whole fight I’d have to wait, probably until Poppy moved out of the apartment, maybe even until she left the city for good; but considering she’s just landed and has three job interviews and five apartment viewings lined up for later this week, and considering all Poppy has ever wanted is to come live in New York, and considering I should be supportive of her sole desire, maybe her departure isn’t something I should hope for.

🔎 Why it works

This introduction is rooted in concrete action, but the narrator’s indecisive train of thought establishes her tone and hints at her relationship with Poppy. The way she talks about her own appearance at the start of the scene suggests not joyful self-love, but bitter vanity rooted in comparison. It suggests that her relationship with Poppy sparks some jealousy or insecurity, though we’ll need to keep reading to understand exactly where that comes from.

Later in the paragraph, though, the narrator changes her tune. She decides that maybe she should support Poppy’s goals instead of hoping for her departure — that “should” suggests self-judgement — she hasn’t miraculously changed her opinion, but now she feels guilty about it.

The back-and-forth hints at a complicated relationship between Poppy and the narrator, but we need to read on if we want to uncover exactly what’s going on between them.

✍️ Master this technique

If you’re going to start in a character’s head, it’s usually a good idea to make sure that the internal monologue is rooted in concrete details. Showing a character thinking about something — whether it’s a relationship with someone else, a problem at work, or the meal they’re preparing as they think — makes for an introduction that drives the story forward.

You’ll notice a running theme here: the key with this kind of introduction is balance. Give enough perspective to reveal something about the narrator, but be careful about looking too far inward without offering enough context.

There’s no single “right” way to start a scene, but by incorporating compelling details, provoking a question, and giving enough context to bring your readers into the story, you can ensure that they keep on reading to see what happens next.