Learning how to write horror is a useful for any writer. The genre contains storytelling elements that are useful beyond it. Read a concise guide to horror. We explore what horror is, key elements of horror, plus tips and quotes from masters of horror film and fiction.

What is horror? Elements of horror

The horror genre is speculative or fantastical fiction that evokes fear, suspense, and dread.

Horror often gives readers or viewers the sense of relief by the end of the story.

Stephen King calls this ‘reintegration’. Writes King in his non-fiction book on horror, Danse Macabre (1981), about the release from terror in reintegration:

For now, the worst has been faced and it wasn’t so bad at all. There was that magic moment of reintegration and safety at the end, that same feeling that comes when the roller coaster stops at the end of its run and you get off with your best girl, both of you whole and unhurt.

Stephen King, Dance Macabre (1981), p. 27 (Kindle version)

I believe it’s this feeling of reintegration, arising from a field specializing in death, fear, and monstrosity, that makes the danse macabre so rewarding and magical … that, and the boundless ability of the human imagination to create endless dreamworlds and then put them to work.

A brief history of the horror genre

Horror, like most genres, has evolved substantially.

Modern horror stories’ precursors were Gothic tales, stretching back to the 1700s. Even stretching beyond that, into gory myths and legends such as Grimm’s folktales.

In early Gothic fiction, the horrifying aspects (such as ghostly apparitions) tended to stem from characters’ tortured psyches. For example, the ghostly shenanigans in Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw (1898). It was often ambiguous whether or not supernatural events depicted were real or imagined by a typically unreliable, tortured narrator.

More modern horror turned increasingly towards ‘psychological horror’. Here, the source of horror is more interior. Or else an external monster or supernatural figure is no figment but completely real.

See Noël Carroll’s The Philosophy of Horror: Or, Paradoxes of the Heart for further interesting information on the genres history, as well as Stephen King’s Danse Macabre.

8 elements of horror

Eight recurring elements in classic and contemporary horror, from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) to the contemporary horror films of Ari Aster, are:

- Suspense (the anticipation of terror or bad things). Horror builds suspense by evoking our fear of the known (for example, fear of the dark). Also fear of the unknown (what could be lurking in said dark).

- Fear. The genre plays with primal fears such as fear of injury, accident, evil, our mistakes, whether evil faces accountability (see Thomas Fahy’s The Philosophy of Horror for more on the philosophy of horror and moral questions horror asks).

- Atmosphere. Horror relies extensively on the emotional effects of atmosphere. Just think of the claustrophobic atmosphere of the ship, the aliens’ human-hunting paradise, in the Alien film franchise.

- Vulnerability. The horror genre plays with our vulnerability, makes us remember it. Horror often asks ‘what if the other is overtly or insidiously malevolent? In asking this, it reminds us of the values of both caution and courage.

- Survival. Many horror subgenres explore themes of survival, from zombie horror to slasher films. Like tragedy, survival stories explore the rippling-out consequences of making ‘the wrong choice’.

- The Supernatural. Horror stories also plumb the unseen and unknown, terrors our physics, beliefs and assumptions can’t always explain.

- Psychological terror. Horror typically manipulates the perceptions of readers/viewers (and characters) to create a sense of unease. ‘What’s thumping under that locked cellar door?’

- The monstrous. Whether actual monsters or the monstrous possible in ordinary human behavior, horror explores the dark and what terrifies or disgusts.

Further elements and themes that appear often include death, the demonic, isolation, madness, grief and revenge.

What does horror offer readers/viewers?

In The Philosophy of Horror (2010), Thomas Fahy compares horror to a reluctant skydiving trip taken with friends, referencing King’s concept of reintegration, the ‘return to safety’:

In many ways, the horror genre promises a similar experience [to skydiving]: The anticipation of terror, the mixture of fear and exhilaration as events unfold, the opportunity to confront the unpredictable and dangerous, the promise of relative safety (both in the context of a darkened theater and through a narrative structure that lasts a finite amount of time and/or number of pages), and the feeling of relief and regained control when it’s over.

Thomas Fahy (Ed.), ‘Introduction’, The Philosophy of Horror (2010).

Horror also appeals to the pleasures of repetition. The darkly amusing absurdity and existentialism of how characters are bumped off one by one in a slasher film, for example.

Audiences also flock to horror for tension (produced by suspense, fear, shock, terror, gore and other common elements), personal relevance (the way horror explores themes we can relate to), and the pleasure of the surreal or unreality.

What do you love about the horror genre? Tell us in the comments!

How to write horror: 10 tips (plus examples and quotes)

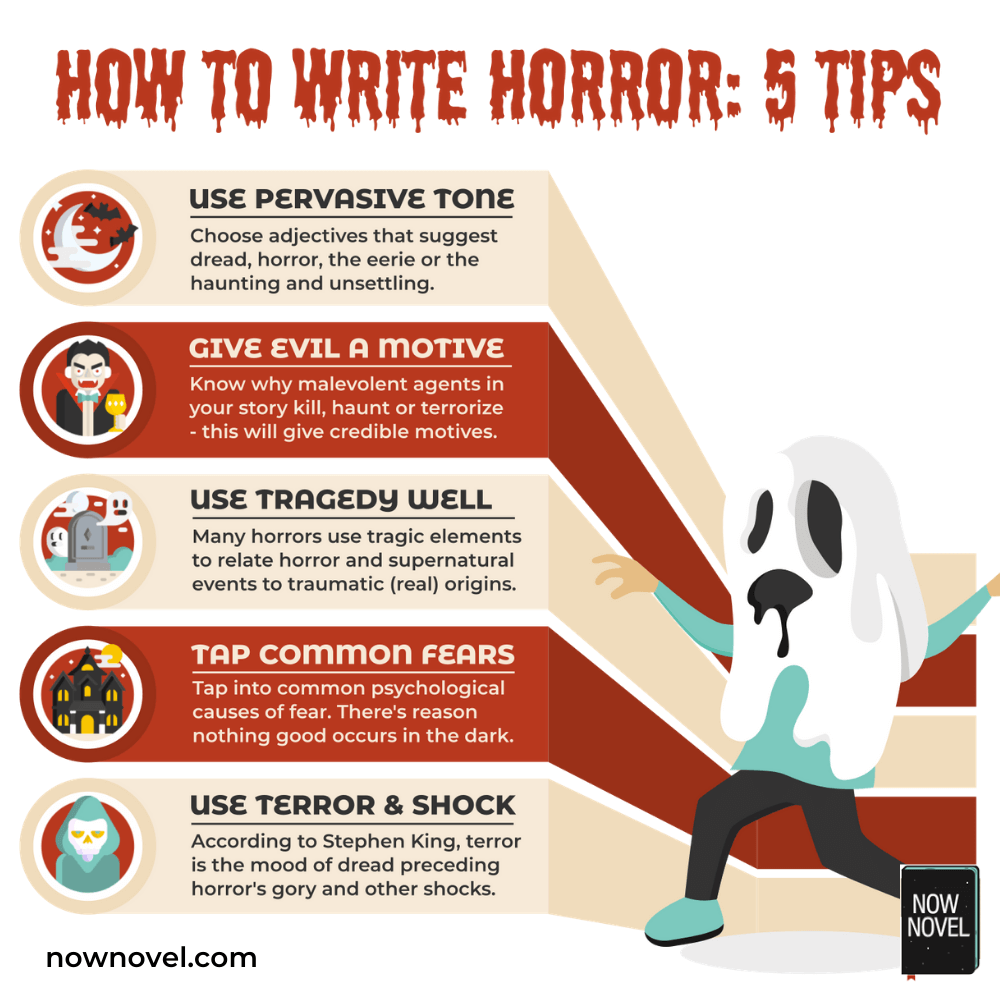

Explore ten ideas on how to write a horror story:

- Pace the big horror scares for suspense

Jump scares and sudden gore might punctuate the story, but if they appear every page they risk becoming predictable.

- Use characterization to make readers care

Who in your ensemble will your reader or viewer want to survive or triumph over horrifying events, and why?

- Make the known scary, not just the unknown

Often horror flips between everyday fears (a young couple’s fears about becoming parents, for example) and a symbolic, scarier level.

- Don’t feel you have to explain everything

Great horror stories often live on in reader/viewer debate about what ‘really’ happened. They reward rewatching.

- Play with the terror of plausibility

Horror stories make terrifying events (such as an author being abducted by a homicidal superfan in King’s Misery) seem plausible. We believe their worlds.

- Scare horror audiences when they least expect

Who can forget the infamous shower scene from Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho? Horror often scares us where we think we’re safest.

- Deepen the story with layers of fear

Play with multiple layers and levels of fear – fear of the known, unknown, of real monsters and the make-believe monsters of perception.

- Add subtler hints of something wrong

What will create that feeling that something’s just a little off, unexpected?

- Balance gore with the unseen (subgenre depending)

Some horror subgenres (e.g. splatterpunk or slasher horror) go all-out on gore. Violence isn’t the only way to unsettle your reader, though. Play with the fear of the unseen – imagination can supply the possibilities.

- Tell a good story first, scare readers second

Focusing solely on scaring readers may end up with a story that is more style and provocation than substance. Think about character and story arcs, using setting to create tone and atmosphere, other elements that make up good stories.

Pace the big horror scares for suspense

Let’s explore each of the preceding ideas on how to write horror. First: Pacing.

As in suspense, pacing is everything in horror. Good pacing allows the build-up, ebb and flow of tension.

See how the script for the classic 1973 horror film The Exorcist (adapted from William Peter Blatty’s 1971 novel of the same name) begins? Not with immediate, obvious demonic possession, but the suspense of an archaeological dig. There are no jump scares, and no gore – just quiet unease.

GET YOUR FREE GUIDE TO SCENE STRUCTURE

Read a guide to writing scenes with purpose that move your story forward.

Learn morePacing in horror-writing example: Slow-building tension in The Exorcist

EXTERIOR- IRAQ- EXCATVATION SITE- NINEVEH- DAY

The Exorcist screenplay. Source: Script Slug

Pickaxes and shovels weld into the air as hundreds of excavators

tear at the desert. The camera pans around the area where

hundreds of Iraqi workmen dig for ancient finds. […]

YOUNG BOY

(In Iraqi language)

They’ve found something… small pieces.

MERRIN

(In Iraqi language)

Where?

This is a long way – geographically and tonally – from a young girl walking backwards downstairs or her head turning around like an owl’s.

A seemingly innocent archaeological dig turns into something more sinister. A link is implied between the statue of a demon unearthed in the dig and two dogs starting to fight:

EXTERIOR – IRAQ- NINEVEH- DAY

The Exorcist screenplay. Source: Script Slug

[…] The old man walks up the rocky mound and sees a huge

statue of the demon Pazuzu, which has the head of the small rock

he earlier found. He climbs to a higher point to get a closer

look. When he reaches the highest point he looks at the statue

dead on. He then turns his head as we hear rocks falling and sees

a guard standing behind him. He then turns again when he hears

two dogs savagely attacking each other. The noise is something of

an evil nature. He looks again at the statue and we are then

presented with a classic stand off side view of the old man and

the statue as the noises rage on. We then fade to the sun slowly

setting as the noises lower in volume.

The suspense in this opening builds up a sense of something horrifying being unleashed on the world unwittingly.

Use characterization to make readers care

Great horror stories may use stock character types, flat arcs. For example, in slasher films where some characters’ main purpose is to die in some creative, absurd way.

Yet subtler horror writing uses characterization to make the reader care.

Part of the truly horrifying aspect of The Exorcist , for example, is knowing that an innocent child is possessed. Tormented by evil through no fault of her own.

The care is palpable in her mother Chris’ (Ellen Burstyn) horror and anxiety in reaction. Empathy is a natural response to having an unwell child (and ‘unwell’ is putting it mildly, in this case).

We empathize with characters grappling with dark forces beyond their control. Life tests everyone with destructive or painful experiences at some point in time. The sense of powerlessness (and tenacity that emerges through that) is a testament to the human spirit, to perseverance.

A horror story itself may have a bleaker reading, of course. Yet we struggle on with the intrepid heroines in their attempts to overcome.

Three horror character archetypes that make us care

In Danse Macabre, Stephen King discusses three common character archetypes in horror and Gothic fiction:

- The Thing – for example, Frankenstein’s monster in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, which expresses pain at having been created.

- The Vampire – often represented as suffering eternal life/return (similar in this regard to ghosts and poltergeists).

- The Werewolf – a horror character who transforms, typically against their will and usually with great suffering, into a beast.

King explores examples of these three horror archetypes from books and films such as Robert Louis Stevenson’s Gothic novella Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886) and Alfred Hitchcock’s seminal psychological horror film, Psycho (1960).

Writes King:

It doesn’t end with the Thing, the Vampire, and the Werewolf; there are other bogeys out there in the shadows as well. But these three account of a large bloc of modern horror fiction.

King, Danse Macarbre, p. 96.

Why horror character archetypes make us care

Horror lovers care about ‘the thing’ archetype often because ‘the thing’, the monster, is misunderstood or blameless for its creation. Think of Frankenstein’s monster, who bargains with his creator for release and freedom.

‘The vampire’ is often a relatable figure because of the inevitable loneliness of eternal life. The vampire is imprisoned by limitations such as not being allowed the rest of death (or even natural pleasures such as sunlight – as glamorous as it might be to sparkle like Stephenie Meyer’s diamante vamps).

King writes about the werewolf and how it represents human duality. The respectable public persona or façade, on one hand, and a world of hidden, private horror on the other. A duality many who carry private trauma can relate to.

Each archetype is relatable on some level. This empathic element makes one care for (or at least understand) the monstrous and inhuman in more literary horror stories. Evil (though some don’t like to admit it) has a face and a backstory, a history of becoming, most of the time.

Read more about how to create characters readers can picture and care about in our complete guide to character creation.

Make the known scary (not just the unknown)

Many horror movies tap into the terror of the known, the common human experience, and not only absurd (but campy and fun) nightmares like clowns hiding in stormwater drains.

Common, relatable parts of familiar human experience to mine for horror and terror include:

- Birth and death (e.g. Rosemary’s Baby)

- Loss and grief (e.g. Hereditary)

- Childhood fears (e.g. It)

- Loss of control (e.g. An American Werewolf in London)

- Ritual and community (e.g. Midsommar)

- Exploring the unknown (e.g. Alien)

Filmmaker M. Night Shyamalan writes in the script for the 2000 film Unbreakable:

Do you know what the scariest thing is? To not know your place in this world, to not know why you’re here. That’s – that’s just an awful feeling.

Often, it is this mundane, relatable element of horror – such as the horror of not having a place in the world – that supplies the psychological or inner aspect.

For example, a bereaved family’s struggle with an occult family history (the outer horror) provides the figurative, metaphorical means to explore the painful reality of grief and intergenerational trauma (inner horror) in Ari Aster’s psychological horror film, Hereditary.

Don’t feel you have to explain everything

Although King’s concept of ‘reintegration’ applies in many horror stories where a sunnier ending promises relief, many modern horror narratives eschew tidy resolution.

It’s a classic ploy in horror series, for example, for there to be troubling alarm bells at the end, inferring that a persistent terror lives on. For example, the jump scare at the end of the original A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) [warning: implied violence, spoilers].

The shock comes through the juxtaposition of an ‘everyone’s safe at last moment’ and terror striking from inside the house without warning, undoing the sense of resolution attained. The main character having woken from the dreams where the bulk of terrifying events occur adds to this false sense of security.

There is no graphic gore or violence. The scene doesn’t show or tell every detail. Instead, the audience has to interpret the event and what it implies about the the status of the conflict between the main characters and the supernatural villain, Freddy Krueger – whether it is truly over.

Play with the terror of plausibility

What is most terrifying is often what is plausible. For example, the crazed fan who abducts her favorite author in Stephen King’s Misery (1987), for hobbling instead of autographs. Celebrity stalking is a well-documented modern cultural phenomenon. It is hard to eyeroll at after John Lennon.

Why is plausibility worth thinking about when exploring how to write horror?

- Suspension of disbelief. If events in a horror story seem plausible (at least for the horror world created), the audience is less inclined to roll their eyes and groan, ‘That would never happen’.

- Relatability. A novel and film such as The Exorcist plays on the natural fear many have that loved ones will fall unwell or depart, in body, spirit or mind.

- Tension and unpredictability: It is more tense and unpredictable when everything is ‘normal’ to start. Ruptures in the fabric of this normalcy create tension, the sense ‘anything could happen’ (that sense requires the bedrock of plausibility first).

Scare horror audiences when they least expect

Like that jump scare in the final scene of A Nightmare on Elm Street, horror often scares the shoes off us when we least expect it.

Take, for example, the infamous shower scene in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), where Marion Crane is attacked in the shower.

The shower, usually associated with privacy, relaxation, is nothing like an abandoned side street, dark wood at night, or other traditionally ‘creepy’ setting. This coupled with the intensity of Hitchcock’s shots – the raised hand clutching a knife – creates a chilling scene.

Horror mastery lies in a push and pull, lulling your audience into a false sense of security, then pulling the rug out from under them when they least expect it.

Tweet This

Get fresh weekly writing tips, polls and more

Join 14000+ subscribers for weekly writing ideas and insights.

Deepen the story with layers of fear

Horror, like other fantastical genres, deals in layers and dualities. In fantasy fiction, we often have a primary world and a secondary one. In horror, the duality is often an internal horror doing a ‘danse macabre’ with an external one.

Says horror filmmaking veteran John Carpenter in conversation with Vulture:

There are two different stories in horror: internal and external. In external horror films, the evil comes from the outside, the other tribe, this thing in the darkness that we don’t understand. Internal is the human heart.

Simon Abrams, ‘The Soft-Spoken John Carpenter on How He Chooses Projects and His Box-Office Failures’, July 6 2011.

In a story using the ‘werewolf’ archetype, for example, the rational, untransformed side of a protagonist may fear the revelation of their monstrous side, the consequences this would have for their daily life (whether they are a literal werewolf or this is figurative). Transformed, the werewolf, like the ‘elephant man’, may experience the external horror and fear of others’ revulsion or animosity (which then feeds the internal, in a vicious cycle).

Having both internal and external conflicts in a horror story moves horror beyond simple disgust and shock tactics. The audience can connect deeper with characters, the cycles of violence they endure or triumph over.

Tapping into common fears for horror writing

If the point of horror writing (and horror elements in other genres such as paranormal romance) is to arouse fear, shock or disgust, think of the things people are most commonly afraid of.

Live Science places an interest choice at number one: The dentist. It’s true that you can feel powerless when you’re in the dentist’s chair. Couple this with the pain of certain dental procedures and it’s plain to see why a malevolent dentist is the stuff of horror nightmares.

Making readers scared creates tension and increases the pace of your story. Even so there should be a reason for making readers fearful.

Here are some of the most common fears people have:

- Fear of animals (dogs, snakes, sharks, mythical creatures such as the deep sea-dwelling kraken)

- Fear of flying (film producers combined the previous fear and this other common fear to make the spoof horror movie Snakes on a Plane)

- The dark – one of the most fundamental fears of the unfamiliar

- Perilous heights

- Other people and their often unknown desires or intentions

- Ugly or disorienting environments

Think of how common fears can be evoked in your horror fiction. Some are more often exploited in horror writing than others. A less precise fear (such as the fear of certain spaces) will let you tell the horror story you want with fewer specified must-haves.

Add subtler hints of something wrong

Returning to core elements of horror – fear, suspense, and atmosphere – how do you make horror scary even when Freddy isn’t dragging anyone through a solid wood door?

Tone and atmosphere emerge in the subtle hints and clues something is wrong.

Hints and signs of horrors to come could include:

- Unsettling sounds. Dripping, humming, chanting, singing, banging, knocking, drumming. What are sounds that imply trouble and the ghastly unknown coming to visit?

- Creepy imagery. What are images and signs that suggest comfort (for example, a lamp burning in a window to signal someone’s home)? Blow those candles out, play with the unhomely.

- Unsettling change. Changes in light, a companion’s tone, a pet’s behavior. Small harbingers of trouble add tension.

- Missing objects. What is not continuous in a way that unsettles and defies expectations? For example, in the reboot of Twin Peaks, an attempt to go home again leads to the dread of everything being different, that sense of ‘you can’t go home again’.

- Discomforting communication. Sometimes horror hinges on a repeated word or phrase (‘Candyman’), or someone saying something creepily unexpected.

The above are just a few ways to imply that something is very wrong.

Balance gore with the unseen (subgenre depending)

Gore in horror has the capability to shock, disgust, make your audience squeamish. Yet a relentless gore-fest may quickly desensitize readers or viewers to the element of surprise.

How much gore you include in a horror will of course depend on your subgenre and story scenario. Slasher stories and subgenres such as splatterpunk (a horror subgenre characterized by extreme violence) will have audiences who demand gore and may lament something tame.

Reasons to balance gore with the terror of the unseen, otherwise:

- Maintaining tension. Periods of calm between violent scenes create suspense, nervous tension for when there’ll be blood again.

- Deepening the story. Great stories with broad appeal take more than blood and guts – meaningful character arcs and genuine scares and horrifying scenes can coexist.

- Artful storytelling. Relying on inference, plot twists, atmosphere, tension for fright and shock is arguably more artful than leaping straight for shock-value. Critical succcesses in the horror genre often don’t rely solely on the cheapest, easiest scares. The story often earns them by building plausibility or deeper symbolic and metaphorical resonance.

Tell a good story first, scare readers second

That last idea boils down to this: Focus on telling a good story, first.

If your sole focus is how most you can shock and manipulate your audience, some may critique this as cheap exploitation.

Some authors – deliberate provocateurs – may wear that label as a badge of pride, of course. Careers are sometimes made in attracting controversy, even bans and censorship for extreme shock value.

Yet the stories that endure often make excellent uses of all the parts of storytelling and encapsulate some of the qualities that make storytelling universal – humanity, insight, the empathy and truth-finding that imagining and exploring ‘dreamworlds’ offers.

Are you writing horror? Join the Now Novel critique community for free and get perks such as longer critique submissions, weekly editorial feedback and story planning tools when you upgrade to The Process.

Now Novel has been invaluable in helping me learn about the craft of novel writing. The feedback has been encouraging, insightful and useful. I’m sure I wouldn’t have got as far as I have without the support of Jordan and the writers in the groups. Highly recommend to anyone seeking help, support or encouragement with their first or next novel. – Oliver

71 replies on “How to write a horror story: Telling tales of terror”

[…] Similarly, the always awesome Now Novel blog has 6 Terrific tips on How to write a horror story that are worth a look. The most important piece of info there, in my opinion is # 5: Write scary […]

Great and helpful post. Its difficult to find helpful, informative posts on horror writing. Thanks.

It’s a pleasure, Alice. I’m glad you found this helpful.

I agree with Alice. This was very useful. Thanks, Bridget.

It’s a pleasure, Melissa, thanks for reading.

As always, an insightful and helpful post, especially regarding the distinction between terror and horror. Love the SK quote! 🙂

Thank you! Thanks for reading. It is a good quote, isn’t it?

Im 11 and working on a horror story with 100 or more pages. this is very helpful. 🙂

I’m impressed, Ethan. Keep going! I’m glad you found it helpful 🙂

Okay, I’m EXACTLY the same age and also working on a horror novel!! I already have 241 pages, though.

Update* im now 13 yayayayyaa owo

I lost the pages and have then finished writing a script for something i cant loose. SO HAPPY ABOUT THIS

Omg hey Ethan and Malachi I’m twelve (right in the middle IG) and working on novels that are going to be between 100 and 300 pages! Good luck guys 😀

Great article. You helped me realise that the short I was working on is actually a novel. Not sure how mind you, but thanks all the same. I’ll sign up now.

Thanks, Gareth! Glad to help.

The article is useful, except for the last part, which totally messed up the beauty of the article. It’s POINTLESS trying to differentiate two things that are mostly used interchangeably. Moreover, Terry Heller’s point makes the whole sense, SENSELESS, because her definition of terror and horror are actually the same except for the subjects to where such emotion is concerned about. Terror is one’s fear for oneself, and horror is one’s fear for others? Are you kidding me?

Both can be subjected to either oneself or to others. Dictionaries and encyclopedias never indicate that horror is what one fears for others alone, because it can be for oneself, too. If Terry cannot differentiate two things, which are not really meant to be differentiated because they are the ultimate synonym for each other, then she doesn’t have to make such an effort. She’s making everyone a fool.

Hi Neil,

Thank you for your engaging response. You raise valid points, and sometimes academic treatments of subjects do over-complicate matters. In light of your comment I’m updating the post since I see now that the distinction isn’t perhaps particularly useful here.

Thanks for the tips. Writing a horror novel for my 1st NaNoWriMo project. This was extremely helpful 🙂

I’m really glad to hear that, Ashley. I hope NaNoWriMo is going well.

I am 12 and have been working on horror since I was 7! So exited to actually get some good info! Thanks!

It’s a pleasure, Aurelia. It’s great that you’re already so committed to your love of writing, keep it up.

Thanks! I am exited to do Nanowrimo and I am am hoping to write a long novel this November. This really helped and extra thanks to the helpful comment!

It’s a pleasure! I hope your NaNoWriMo is going very well.

This has given me more quality advice on the genre than a three year creative writing degree. Best start reading the stuff first then!

Thank you.

Thank you, Neil, high praise indeed. Good luck with your horror book!

… How does one get rid of writers block?

My brain always blanks out when I try and start writing. So annoying! >:c

Sometimes listening to songs with a creepy tone helps

Great advice, Allee. I love listening to music while I work myself.

My advice is to literally just write what comes into your brain, it doesn’t matter if it makes sense or not, that’s what first drafts are for, as long as you’re writing in some shape of form, be it poor or good quality, it’s practice

Thank you.

… My brain is weird. Just now, I’ve been shaken out of my sleep by an intense dream. Seriously. I don’t know what goes on up there, but it’s mad.

Good advice! Maya Angelou said similar about her writing process. Here are some additional tips on moving past a block: https://www.nownovel.com/blog/banish-writers-block/

I’m so happy I ran across this article. I’ve read from more than one story editor that the horror genre is the most difficult genre to master.

I’m glad to hear that, JP. All genres have their challenges but I’d say the best, best, best approach is to read widely in said genre (and others). Thanks for the feedback!

Yeah, if Stephen King can’t terrify or horrify, he’ll gross us out. And he says he’s not proud. In other words, he’ll stoop to the disgust level if he can’t get the others. But this is precisely the problem with the “gross” or “disgusting.” Disgust is not fear. When we are disgusted, we know TOO much. When we are horrified, there is always something we DON’T know. I’m amazed he doesn’t know that. An autopsy gives us disgust because nothing is held back from the viewer. It is not frightening. No one believes, for example, that the body is going to get up from the autopsy table and start attacking the doctor. But if I walk into the autopsy room all by myself and see a dead body on a table, turn away from the body to shut the door, turn back to it, notice it gone, and then have the lights start dimming? Yes. Now I am scared. Why? Simply because I don’t know certain things. I don’t know why the body has suddenly disappeared. I don’t know how a dead person could have moved. I don’t know where the body is right now. I don’t know if that body (if it is actually alive) has good or bad intentions toward me. I don’t know who is dimming the lights and why. It is so much easier to disgust the reader than to horrify him. It takes more cleverness to hold back information from the character and the reader than to let everything gush forth in blood and guts. In The Hound of the Baskervilles, for example, there is more fear to be found in the inscrutable nightly crying of the butler’s wife than in many of our modern horror films put together. Why is she crying? Why only at night? Why is she doing looking out of the window into the dark each night? The source of fear is in the unknown.

Ultimately, King does know and it is a show vs tell metaphor. You have to read his biographical On Writing because no one explains it correctly. Terror is the psychological aspect of the story. Horror is the stories physical manifestation of the terror. Disgust is the actions of horror. Showing the actions of horror kills all suspense immediately. I like to explain it to my students and listeners as if Terror and Horror are the brake and Disgust is the gas. It’s like the old story of the escaped lunatic with a hook were a young couple go out on a date. While driving to Make Out Lane there is a report on the radio about an escaped killer with a hook running around killing people that the only the girl hears. As the girl and boy are making out she sees a shadow and the boyfriend sees nothing. Then there is the screeching sound on the outside of the car. That’s terror. The boyfriend gets out and inspects his car in the dense fog. The girl loses sight of the boy as he walks toward the rear, building on the terror. There is another screech along her door, terrorizing her. She calls out the boys name and he doesn’t respond, building on the terror, possibly toward horror if the boy doesn’t return. Then he does. He leaps into the car and jerks it into reverse and pulls away from the scene at mach-5. When they arrive back at her house, they find a hook dangling from the passenger door handle, the horror. King describes this little story as the perfect short horror story. However, in some later versions of the story the girl jumps in the driver’s seat and pulls off without the boy. When she gets to her home she finds a bloody hook dangling from the door with a bit of gut on it, leaving the girl and the audience disgusted. as the tension and suspense are deflated.

This is very helpful. My 8th grade English teacher is holding a contest for writing a short (750 to 3,000 word) horror story, so I am researching the elements of horror and how to incorporate them into my work. This article is by far one of the more helpful ones I have found in finding ways to create fear, shock or disgust in the mind of the reader. Thank you!

Hi Margaret,

Thank you for this feedback. I’m glad to hear you found this article useful. I hope you won the contest 🙂

“…his skin distinctly yellowish in colour.”

Far from being exemplary in any way, this is actually terrible, hack writing.

If something is “yellowish,” it cannot be “distinctly” so. It’s either distinctly yellow, or “yellowish.”

Likewise, “in color” is flabby and redundant. Could the skin be “yellowish” in shape or size? Could it be “yellowish” in cost or weight?

This page is distinctly whiteish in color.

See how weak and flabby that is?

To be fair, there is a lot of good information on this page. But Clive Barker is a dreadful writer, and should never be cited as an exemplar of good prose.

Hi Sharkio, you raise a very good point. I second your edit of just saying ‘yellowish’ and cutting in colour and am tempted to add a note on not taking the letter of his prose as exemplary, but rather the spirit 🙂 I agree that although the atmosphere and tone are there, the prose is weak in places. There’s also the question, though, of whether we can/should apply ‘literary’ standards to genre fic where these and other ‘sins’ are more widely accepted 🙂 Thanks for the thoughtful engagement with this detail.

Are you crazy? There is no writer at the top of their game as Barker was in the 70-90s. His influence is on everything today.

Thanks for sharing your perspective, H Duane 🙂 Just goes to show that everyone has different preferences. He is regarded as one of the modern masters of horror. I suppose genre fiction readers might also be more forgiving of certain stylistic choices than literary readers.

Some good tips after writing 2 love stories and a mystery now I am trying for some horrer story and this will help me such a good information

Thanks, Sidhu. That’s an interesting genre leap, but many horrors do have both elements. It’s a weird trope to me how often the romantic leads are the first to go in slasher flicks. You’d think writers would keep them to add romantic tension to the mix. I hope your story’s coming along well.

I just finished writing my first horror script/ screenplay… I checked this list just to see if I maybe left elements out that I should include or if I was on the right track and I’m proud to report that my script has it all… Once my film finally sees the light of day, I hope all horror fans are satisfied…

Hi Timothy, I hope so too! Best of luck with the next steps, please update us about what comes of it.

I am attempting to write a horror story where the main character is possessed and is writing in a diary like format as it occurs, and begins committing murders, how do I accurately capture the descent into madness?

Hi Evan, thank you for sharing that. It’s an interesting challenge. I would suggest a shift in style and tone in his writing. For example, perhaps they use stranger metaphors, repeat themselves more, their sentences become more fragmented, there’s the occasional odd word by itself on a line, lines or sentences that don’t make complete semantic sense but have an eerie undertone (I think of the classic phrase ‘The owls are not what they seem’ in David Lynch’s Twin Peaks).

I hope this helps! Good luck.

Thank you, this was very useful. I appreciate your enthusiasm and encouragement.

It’s my pleasure, Evan, glad to help. Have a great week.

Wow this was really helpful thanks

I’m glad to hear that, Rene. Thank you for the feedback!

I wanted to write a psychological thriller story for a youtube channel. I am glad I found help from here. Thank You.

It’s a pleasure, Suyasha! Thank you for reading and good luck creating your story for YouTube.

I appreciate the reference to ’cause and effect’ for any level of villainy. The more complex the villain, the more interesting the story. Anything that steps out of the dark and says, “Hi, I’m evil. I’m here to destroy everything for no apparent reason,” flattens the scene. I think your point about motivation is key to getting people engaged in the fantasy. I think that this will heighten the tension in my current story. Thank you.

Hi Deborah, thank you for sharing your thoughts. Agreed, a complex villain also tends to be less predictable which inherently builds more suspense, as (compared to a Bond villain, for example), they’re more textured and unknowable, less of a trope or archetype. I’m glad you found these ideas helpful to your current story, good luck as you proceed further!

Totally agree with you Joseph Pedulla. You summed it up perfectly! Gross is not scary. I like scary. Stephen King is talked about all the time like the all-time best horror writer. I have tried reading some of his work and I find it mind-numbingly boring. I like the story to move along; don’t give me a whole bunch of description!! Read Darren Shan’s ‘The Cirque Du Freak Series.’ Absolutely amazing!

Thank you. I appreciate the elaboration on each hint. I also think your arguments make sense AND can be helpful to many indie-authors & startup writers alike.

Thank you for your feedback, Andre. I’m glad you found our article helpful!

Was looking for some takes regarding this topic and I found your article quite informative. It has given me a fresh perspective on the topic tackled. Thanks!

Please see also my blog,

Getting to Know the 4 Incredible Authors of Horror Fiction

Hope this will help,

Thank you, Joab. Thanks for sharing your horror writing blog.

[…] How to Write a Horror Story: 6 Terrific Tips […]

This is quite interesting and I can see how it relates to film more readily than to a novel – perhaps due to the many film examples and the visual quality of the ‘jump scare’, etc. I can see that film examples are very useful, however, I’m having trouble relating this to crafting words on a page as opposed to images on a screen.

Hi Rachel, thank you so much for this useful feedback. It’s interesting how much film and narrative fiction have influenced each other in this specific genre, but this is useful to me – I will work in more examples from horror lit in an additional section when I have a moment. Thanks for helping me make this article better and for reading.

Interesting! I may add some horror prompts to Craft Challenge. You did forget to mention the terror of never finishing a book, missing tons of errors, writing something right after someone else does it, and getting your book idea stolen 😉 Although I suppose they’re preferable to a gruesome death, or drowning, or grasshoppers (don’t judge me) 🕷️🪓🩸

I’m now trying to remember which of those fears horror authors’ writer characters (e.g. in Misery) have 🙂 I’m going to have to have a look at that. OK, I’m with you on the grasshoppers. My aunt lives near the mountain and they get these very angry-looking green ones my aunt calls ‘Green [redacted]s’ 😉

Also please do, I’ll also think up some horror prompts to share as well (another section for this article in version 2.1).

Oh, I forgot one! The fear of every critique starting with “I don’t like this genre.” 😳

Haha I love that, Margriet. A relatable fear, I would say.

How much room for humor do you think there is in the horror genre? Do you think you could write a horror novel that has a high percentage of humor Vs. horror/gore and still call it a horror novel?

This is a great question, Scott. I really am not a horror expert myself (sometimes I write far out of my comfort zone here which requires a little more research). But if I think of Tim Curry’s performance as It, for example, how he fills the character with this wild humor and characterization that made many prefer the original to the remake, I would say horror has as much capacity for humor as you want it to have. Comedy horror is a thing, with zombie spoofs and the like produced, so you could always market a comedy horror title in both categories. I think part of the natural crossover is that jump scares, campy villainous dialogue, or see-it-coming-from-a-mile tropes often make audiences laugh, too.

I’m working on one to it’s very wierd and it’s called Toony and The Ink Machine Yes I know kind of ripoff of Bendy and The ink machine.

Fabulous title, Silas! Wishing you the best with the writing process.