Creating a story outline is not for everyone. Yet it is a useful way to scrutinize and expand your story idea. A way to find more material, and create a story structure template that guides your draft. Learn how to write a plot outline with these seven plotting techniques:

7 popular story outlining methods:

- Start with a synopsis

- Summarize scenes and chapters

- Use cards, corkboards, whiteboards

- Plan action and reaction beats

- Divide into purpose-driven acts

- Modify the Hero's Journey

- Do a draft zero

Let's explore how to make a story outline in further detail:

Start with a synopsis

Putting limits and parameters in place for a creative project is one of the hardest parts. You're making choices that will direct, to a degree, the progress and destination of your project, after all. Total freedom may feel daunting.

A freer, looser first step often helps to ease into making further creative decisions.

Once you have a central idea for your story, write a synopsis detailing everything you know so far.

Write down the starting scenario or situation that leads to the inciting action - the events that set your story in motion. Note any obstacles or adversaries you already know will feature.

This may seem a daunting task when you haven't written any part of a draft yet. Leave out anything you don't know yet.

The free 'Central Idea' section of Now Novel's step-by-step story dashboard guides you through finding a concise, central idea. There is also further guidance to write a helpful synopsis and fuller outline.

Summarize scenes and chapters

A plot outline is helpful to structure your story into scenes and chapters. Scenes are 'a sequence of continuous action in a play, film, opera, or book' (OED). We've written before on how to structure scenes around concrete, clear story events.

Writing scene summaries ahead of drafting your scenes in greater detail is a helpful way to maintain focus. It will help you ensure every scene is driven by clear purpose.

When you know why you're writing a scene (how it serves the broader story) it's a little easier to decide what to include. Also what to leave for another scene or chapter (or leave out entirely).

To summarize scene and chapter ideas and move them around and sequence story events, Now Novel's scene builder is a useful tool. See our article on creative ways to use this browser-based story outlining tool.

Use cards, corkboards, whiteboards

Writing is a very verbal process. Many writers find it helpful to add a visual element to plotting, because this helps us to see the structure of a work of fiction (or non-fiction) laid out.

Vladimir Nabokov famously wrote sections of stories on physical index cards that he would then reshuffle to find novel possibilities for plot lines and the order of his stories' events. Said Nabokov:

The pattern of the thing precedes the thing. I fill in the gaps of the crossword at any spot I happen to choose. These bits I write on index cards until the novel is done. My schedule is flexible, but I am rather particular about my instruments: lined Bristol cards and well sharpened, not too hard, pencils capped with erasers.

Vladimir Nabokov, interviewed by Herbert Gold, 'The Art of Fiction No. 40', The Paris Review, quoted by Colin Marshall for Open Culture

Outlining a story on cards, notes on a corkboard (whether analogue or digital like our scene builder tool) is a helpful way to get physical with your plotting process.

Plan action and reaction beats

The previous sections of this guide to how to outline a book describe plotting the macro or large-scale elements of your story.

What if you don't want a plot structure template, but rather an outlining method that is flexible and adaptable to any genre?

Enter story 'beats'. What is a beat? It's a screenwriting term that describes 'a moment that propels the story forward and compels the viewer to take stock of what could happen next' (definition via Masterclass).

To take an example, in a classic fable such as 'The Three Little Pigs', you have action and reaction beats such as:

Action: Mother pig sends her grown up piglets out into the world

Reaction: Without their mother's shelter, each pig builds a house of different materials based on personal qualities such as their different work ethics.

The thing to note about outlining a story in action and reactions is that a reaction beat is:

- Relevant to the preceding action. Because the pigs now have to fend for themselves, they must build shelter. Reaction shows the consequences of action

- A passage towards further action or complication. The pigs having varying work ethics is building their homes proves crucial to the story, since only the hardest-working pig builds a home strong enough to withstand the wolf, the story's antagonist

Outlining your story simply like this in duos of action and reaction (where reaction propels new actions) is a smart way to simplify plotting. It's a happy compromise between detailed planning and looser plotting methods.

Writing coach Romy Sommer shares more on action and reaction as a story outlining tool in this extract from our monthly writing webinars:

Divide into purpose-driven acts

It is almost impossible to talk about story outlining methods without talking about structure.

Structure is not necessarily something you put in place first. Yet if you do write to a broad structure you may find it helpful as you will have an outline for what events (broadly) should occur in each section of your book.

A common approach to plot outlines is to combine three-act structure with scene and chapter summaries (as described above) or other methods.

What is three-act structure?

Briefly, three-act structure is a concept borrowed from stage plays, acts being the sections of continuous action in a play between curtains or set changes.

In three-act structure, each act contains the following:

Act I: The setup, including exposition (the introduction of the story's setting and world) and the inciting event (the incident that sets the story in motion).

Act II: The development or 'confrontation', in which there is rising tension and/or conflict. In Shakespeare's Othello, for example, the middle is when Iago (the antagonist) stirs up conflict between most of the other characters in the play.

Act III: This act typically builds to a climax (and often a so-called 'dark night of the soul' where a protagonist is at their lowest point or victory/success seems most unlikely), followed by resolution.

As a broad approach for outlining your story, three-act structure is useful as it helps you ensure each third of your story achieves something important with respect to your plot (and moving the action forward).

Modify the Hero's Journey

The hero's journey is based on the study of myth by writer and scholar Joseph Campbell. Campbell believed that all world myths included some similar elements. While there may be as many as 17 steps, the hero's journey can be divided into three main sections like three-act structure.

In Campbell's version, these are departure or separation, initiation, and return.

While Campbell used the language of myth and fantasy to describe the hero's journey, the structure can be used for realist fiction as well.

Outlining a story using the Hero's Journey in three acts

In the first section, the protagonist receives a call to action and refuses it. The protagonist then encounters a mentor or supernatural aid and crosses the threshold into a different world.

In the second act, the protagonist undergoes a series of trials or temptations. For a romance, this could be the allure of an ex that comes back into the picture, for example (forcing the protagonist to choose between two would-be partners).

In the final act, the protagonist must return to the ordinary world. Typically (in a quest narrative, at least), the protagonist triumphs in the end.

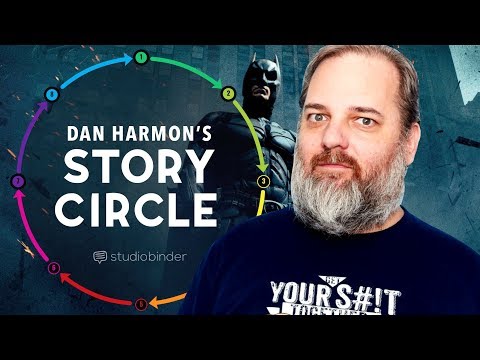

Example of an outlining method based on the Hero's Journey - Dan Harmon's Story Circle

Dan Harmon's 'story circle' is an example of a modified Hero's Journey structure. Harmon explains the simplified, 8-step story template and its flexibility in this video for Studiobinder:

Do a draft zero

Some writers simply do not want to outline. However, even if you prefer to write by the seat of your pants, there is a kind of plot outline you may find useful.

This is what we call a zero draft or discovery draft.

This draft is too unstructured to be even a first draft, but it is far more extensive and detailed than the above outlines. In fact, it can run to 100 or 200 pages.

The crucial aspect of a draft zero is to write your draft as quickly as possible. You can skip entire swathes of your story and leave notes in their place.

The discovery draft is a helpful exercise if you've struggled with outlines but find you get bogged down while trying to write a novel without the safety net of one.

Need a more structured process? Make real progress in six months with weekly workbooks, daily writing sprints, and a constructive, supportive community on Now Novel's Group Coaching course.

Thanks for outlining various outlines. :P I find it so daunting to think that I should scribble out all the twists and turns of a story before they really come alive in me. I shall attempt a few of these and see if I can find a dynamic process for myself.

Julie - About 10 years ago

It's a pleasure, Julie! It is a challenge, but if you're more of a pantser you could always try the draft zero approach or writing the story as a sequence of scene synopses where you're focusing on event rather than fleshing out your world for the first run. I hope you find one that works for you. B

Bridget At Now Novel - About 10 years ago

Love the articles on your blog! So helpful! I really wish I knew how to outline but I just don't get it. How can I list all the stuff that's supposed to happen - much less where in the book it's supposed to happen - if I don't even know what is supposed to happen before I start writing? Even in college, I would write full papers (I'm talking 15-30 pages) first and then write the outline that the profs always insisted on having because it was the only way I knew what to put where. I completely understand the need for an outline and want so desperately to be able to write and use them but I just have never been able to do it. Maybe I just need a super in-depth course on how to outline, along with a sample that the teacher does right along with me.

Rayna - About 10 years ago

Hi Rayna, Thank you for reading! It sounds to me as though you are more a pantser than a plotter by nature, and that's fine too - the important thing is to find what works for you. You may find if you force yourself to try come up with the basic structure of a story beforehand, even just as an exercise, that it helps to add a certain degree of structure to your writing craft. Thanks again for reading and weighing in on outlining.

Bridget At Now Novel - About 10 years ago

This article is very helpful! I Writing a first draft has never been an issue for me - it is the 2nd go around in which I get stuck on. I use excel to create a character list so I don't forget who has blue eyes or blonde hair! HA, ha.. but I've never thought about a plot outline before, because I write chapters and keep most of it in my head but doing a plot outline will help me iron out the actual storyline and rough out what doesn't need to be included in the novel. Thank you for sharing!

Ann Privacy - Almost 7 years ago

Hi Ann, an excel spreadsheet sounds like a useful approach. Thanks for sharing and for reading :)

Jordan At Now Novel - Almost 7 years ago

Useful and interesting article, thanks. I’ve seen references to the LACE method of plot outline / structure too but haven’t been able to find much about it online, any thoughts or info on the LACE method?

Leigh - About 4 years ago

Hi Leigh, thank you. This is actually the first I heard of the 'LACE' method, and couldn't find many resources describing it, but from what I could find the acronym has each letter referring to a plot attribute: L - location-oriented plot unit (e.g. a character entering or leaving a place) A - answer-oriented plot unit (finding the answer to a question, a common type in the Grail legend, for example) C - character-oriented plot (an aspect of a character changes) E - event-oriented plot (an event occurs that changes the status quo). I can see why this is a catchy idea as all stories have combinations of these elements - stories are change, and change with the tension of not-knowing is what makes stories exciting. I think it's a helpful rubric to use for a chapter, to look at that list and ask yourself, for each chapter, 'does it have this element?' (i.e what aspects of the story change each chapter - and is there sufficient change and forward momentum?). I'm sure there's more to this method than the little I could find, so if you have an original source that goes into detail about it, please share it with us. Thank you for reading our blog.

Jordan - About 4 years ago

The "LACE method" is a variation of the MICE Quotient (Milieu, Inquiry, Character, Event) invented by Orson Scott Card (discussed in his two nonfiction books on writing) and recently popularized by Mary Robinette Kowal. Here's a link to one of her lectures on the subject: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=blehVIDyuXk

Ray W - Almost 4 years ago

Hi Ray, thank you for this share. I'll definitely look into Orson Scott Card's approach.

Jordan - Almost 4 years ago

Jordan, this was a great post. I’m glad that I outlined the first book and now the sequel in progress. I’m using Snyder’s 15 Beat Sheet and have the story lined up. It helped to know where certain scenes I had in mind should be placed. It was a lot of work, but it’s paying off in the end. 📚 Christine

Christine E. Robinson - Almost 3 years ago

Hi Christine, that is a great beat sheet (I really enjoyed Saves the Cat Writes a Novel too which has more adapting of the screenwriting terms to a novel-writing framework). I'm glad to hear your process is paying off 🙌. Thank you for taking the time to share feedback.

Jordan - Almost 3 years ago